The following is an outline of the discipline of prosody, the study of poetic metre. It is probably the area of literary commentary where it is easiest to get bogged down in jargon, and usually a little talk of dactyls, anapaests and secondary stresses will go a long way. But equally there is no doubt that over much of the history of poetry, the concern with metre or 'numbers' has been very high indeed in the minds of readers and writers: one only has to flick through a Renaissance treatise such as Puttenham's

Art of Poesie to see this concern with sound, and to get a sense that previous generations were attuned to nuances of rhythm to a degree we perhaps cannot now recapture. In any case, the basics of the matter are offered below for the bold and curious, and suggestions for other sources are added to placate the dissatisfied.

Syllables

Words in English divide into units of sound which we call syllables: win-dow, coll-ect, ten-der (2 syllables each); fasc-in-ate, cum-ber-some, dis-as-ter (3); ex-clam-a-tion, con-de-scen-ding (4) etc.

A syllable will contain at least one vowel. It may have one or more consonants accompanying it: 'coll' is a syllable consisting of consonant + vowel + consonant. ('Vowel' and 'consonant' aply here to sounds, rather than letters or characters: 'll' is two letters but one consonant sound.)

Stress

When we speak, we naturally emphasise or stress some syllables more than others:

win-dow, coll-

ect,

ten-der,

fasc-in-ate,

cum-ber-some, dis-

as-ter, ex-clam-

a-tion,

con-de-

scen-ding. The stress position is not arbitrary, but subject to habits of speech sound.

Scansion

Poets compose texts in such a way that stresses are normally highly organised within verse lines and longer units. In regular

metre, the arrangement of stressed and unstressed syllables will fall into patterns. These patterns create a particular kind of

rhythm, which can be varied and interrupted for

metrical effect. The study of these patterns and effects is called, to use an old-fashioned term, prosody. Because the key feature of prosody in English is identifying which syllables carry a

stress or accent, the system is called

accentual-syllabic.

When we describe the metre of a line of verse, we first scan it to identify the stressed syllables. Here is the beginning of Canto 4 of Pope's

The Rape of the Lock:

But anxious cares the pensive nymph oppressed,

And secret passions laboured in her breast.

When scanned, the lines look like this (capital letters indicating stress), with the syllables separated:

But ANX-ious CARES the PEN-sive NYMPH opp-RESSED (10)

And SE-cret PASS-ions LA-boured

IN her BREAST. (10)

I have used a smaller size for

IN (line 2), because its stress sounds lighter than the other capitalised syllables: it carries a secondary stress (though stress has been divided into more than two grades). It is in fact a common effect that where there are five stressed syllables in a line, one will be notably weaker and take a secondary quality.

So far, we have marked line one of the extract as having ten syllables, made up of five unstressed and five stressed, and line two as following the same pattern (with a qualification noted on 'in'). If we use the conventional symbols of / for stress and x for unstressed, we can represent this as the following sequence:

x/ x/ x/ x/ x/

This sequence is clearly ordered and not random, and its repetition in two successive lines suggests strongly it is not arbitrary. It is a pattern consisting of the x/ unit, repeated five times. With vertical lines between each unit, we see how it maps onto the line of verse:

But ANX |-ious CARES | the PEN-| sive NYMPH | opp-RESSED

A poetic line which behaves according to a regular accentual metre like this is said to

scan (and

scansion is another term for metre).

Feet

The basic unit of stressed and unstressed, repeated to form a pattern, is known as a

foot. Metrical feet are oblivious of meaning: they correspond to groups of syllables, and words can cut across them. In traditional scansion, feet are designated with Greek words. This is far from ideal, both because Greek is today an obscure language even to most educated people, and because the Greek language works very differently from English: Greek and Latin poetry are

quantitative, that is to say their syllables are long and short, and to take words used to describe this state of affairs as the tools with which to describe a different sound world where syllables are stressed or unstressed is a kind of category error. Nonetheless, the error is so long ingrained and enshrined in textbooks that it seems inescapable. And, it must be said, while the terminology is not ideal, there is still much useful work that can be done with it.

Iambic Pentameter

Pursuing Greek terms, the unit of x/ (stress unstress) is an

iamb. The line from Pope we have been concentrating on has five iambs, making it a p

entameter (words ending in -meter count the number of feet in the line: pentameter means 'five feet'

and that is all it means). The

iambic pentameter is the most common line in post-medieval English poetry, long enough to encompass interesting thoughts while remaining memorable, and at the same time anchored in the natural rhythms of speech (The pentamter functions equally well at different speech registers. Examples of colloquial pentameter: I wonder if they'll call us when he comes, I've read this thing at least a thousand times! Just text me and I'll come and pick you up). The iambic pentameter is used in many rhyming verse forms; verse in non-rhyming iambic pentameter is called

blank verse (examples are

Paradise Lost and most of the dramatic verse of Shakespeare).

To recap, the three stages of describing the metre of a line are:

- Identify stressed syllables

- Identify the basic kind of foot into which the line can be broken down

- Count the number of feet to give the type of line (note: count the feet, not the syllables).

Here are the most common feet in English with their Greek names:

iamb x/ (forGIVE)

trochee /x (WINdow)

spondee // (I've got

BAD NEWS)

pyrrhic xx (MUCH

of the TIME)

anapaest xx/ (InterrUPT)

dactyl /xx (CHARacter)

The line lengths are designated as follows:

1 foot: monometer

2 feet: dimeter

3 feet: trimeter

4 feet: tetrameter

5 feet: pentameter

6 feet: hexameter

7 feet: septameter / fourteener

Verse lines can thus be described in terms of their feet, and the number of feet in a line:

I wonder if she's there (I WONder IF she's THERE) = iambic trimeter

How the time is running past us! (HOW the TIME is RUNNing PAST us) = trochaic tetrameter

Tetrameters and pentameters are far the most common in English verse. Mono, di, hex and sept are rare.

Pitch

The voice usually rises in pitch when it stresses a syllable. Hence, iambs and anapaests, which end in a stress, naturally create a rising rhythm. Trochees and dactyls, which move from stressed to unstressed, create a falling rhythm. These two effects can be counterpointed to create a wave-like sensation, and prevent the iambic line from becoming noxiously jaunty. The couplet from Pope is an example. The only way to get a word like 'window' (/x) into iambic verse is to make it cross from one foot into the next (An |xious). Pope uses several such trochaic words, and the effect is to slow the verse down, creating a feeling of falling against the natural rising rhythm of the iambs. Though this aural pattern is meaningless in itself, it usefully colours the content of the line, and here perhaps helps us to imagine the mental labour and anxiety of the 'nymph', to feel her vexed sighings (though this reading may simply be an example of 'reading in' the sense of the words into their rhythmic utterance; sound effects diviorced from lexical meaning seem to have no real effect at all):

But

ANX |-ious CARES | the

PEN-| sive NYMPH | opp-RESSED

And

SE | cret PASS | ions LA | boured IN | her BREAST.

Syntax

The second line here noticeably goes into a trochaic rhythm, to come out of it in the last foot. (Returning to the weaker 'in', we might even scan this as a pyrrhic - two unstressed syllables).

In this example, the syntax corresponds to the metre: each line contains a single grammatical sentence, linked by the conjunction 'And' at the start of line 2. Often, though, poets will set tensions between the verse line and the syntax, with sentences flowing over several lines, starting and ending mid-line, and local rhythms forcing themselves against the dominant general pattern. Milton does this constantly, and it is a characteristic feature of writers in what we may call the baroque style. But in any period it is a general effect to look out for: the sentence rhythm - the general shape and natural emphases of the sentence - will be in some kind of relationship, friendly or tense, with the verse rhythm, demarcated by individual lines. In these lines from Donne, we can hear the energies of the sentence struggling against the prim compartments of metre and line as the cosmic vision is released into words:

At the round earth's imagined corners, blow

Your trumpets, angels; and arise, arise

From death, you numberless infinities

Of souls, and to your scattered bodies go;

all whom the flood did, and fire shall, o'erthrow ...

Against this emotive effusion, the classical, Augustan line counters with well-bred lines of shapely poise and balance. 'To Penshurst', by Donne's contemporary Ben Jonson, celebrates the civilised qualities of the Sidney family, as enshrined in Penshurst, their country estate. We note how the good ordering of the land is represented in the orderly syntax, rhyme and metre:

Thy copse too, named of Gamage, thou hast there,

That never fails to serve thee seasoned deer

When thou wouldst feast or exercise thy friends.

The lower land, that to the river bends,

Thy sheep, thy bullocks, kine and calves do feed;

The middle ground thy mares and conies breed.

Variation

Verse lines can vary without changing their scansion. In these lines by Sir Philip Sidney, we feel the tedious ascent of the moon in the heavy tread of the iambic feet:

With how sad steps, Oh Moon, thou climb'st the skies,

How silently, and with how wan a face!

Of course the sense of the lines causes us to slow down but we notice, too, the medial pauses between phrases, and the way the words seem to drag. To stress a vowel is also to lengthen it, and this lengthening is pointed here by thickets of consonants (

steps), assonance (

climb'st, silently), half rhyme (

Moon, wan) and sibilance coming into and out of the vowel (

skies, silently) - all maximising the time value of the syllable and bringing across the sense of effortfulness. The lines are still broadly regular, though we might hear 'sad steps' as a spondee, or on the way to one. By contrast, sense, syntax and the distribution of sounds make these lines by Donne brisker, bringing across the speaker's impatience:

Now thou hast loved me one whole day,

Tomorrow when thou leav'st, what wilt thou say.

Shakespeare offers such variations of phrasing and tempo line by line for the speaking voice, creating an awareness of flexibility against the iambic beat.

Other variations reach for the key to the iambic padlock and unlock it. A few examples will suggest the infinite effects that can be deployed:

To BE | or NOT | to BE, | THAT is | the QUES | tion.

The chief variation happens with the decisive 'That' at the start of the fourth foot. Here instead of an iamb we have a trochee, making it a

trochaic substitution or

inverse (back-to-front)

foot. The line furthermore has 11 syllables (

hendecasyllabic) rather than 10 (

decasyllabic). The extra syllable at the end is a feminine ending (referring, by lamentable tradition, to its weakness) or an

unstressed hyperbeat. Because it has too many syllables for an iambic pentameter, the line is

hypermetrical. The effect of the inverse foot is emphasised by a

caesura or

hiatus indicated here (we know nothing of Shakespeare's actual punctuation) by a comma at the end of the third foot, creating a heavy pause which interrupts the rhythm. For what my intuition is worth, I doubt Shakespeare thought consciously of any of this, any more than a great jazz pianist in performance thinks verbally of chord sequences and key changes: once a craft has been thoroughly internalised, it can be pursued without such painstaking self-consciousness. It is indeed a curious effect of the kind of dissection we are attempting that it seems to attribute to artists toils of ratiocination of which they may have known nothing. But it does not follow that the observations we make of the resulting art are wrong.

Here is another example of a variation:

TYger, | TYger, | BURning | BRIGHT

IN the | FORests | OF the | NIGHT

This famous poem by Blake employs a

catalectic trochaic tertameter:

catalectic = one missing or 'silent' syllable, here the unstressed syllable needed at the end to complete the trochaic pattern (

Tyger, Tyger, burning brightly - this is the trochaic tetrameter used in Longfellow's

Hiawatha to curiously enervating effect). At the line-break, there is no punctuation. Thus the line is not end-stopped and the break constitutes a

run-on, or

enjambment. The effect is not necessarily to speed the verse up. Here, we have two stresses next to each other, either side of the line-break: 'burning

bright /

In the forests'. In fact, the enjambment creates a pause, allowing us to hold the image of the burning tiger in our minds before extending the vision into the forest.

The next example is from Shakespeare. Typically, it is open to many different readings, one reason that the plays allow for repeated productions. The line is from King Lear's famous 'Oh, reason not the need' speech:

If ON | ly to | go WARM | were GOR |ge-ous,

WHY, NA | ture NEEDS | NOT what | THOU GOR | geous WEAR'ST.

To 'save' the metre here, 'Gorgeous' has to be given its full three syllables in the first line, while it is compacted into two in the second. Similarly, words like

imagination can be 5 or 6 syllables according to metrical need. In the reading I have suggested above, the second foot of line 1, 'ly to' is a

pyrrhic substitution, while two feet in the second line are

spondaic substitutions. The foot 'NOT what' is a now familiar

trochaic inversion. The net effect is to feel the iambic current being short-circuited, bringing out a stuttering, interrupted rhythm we may associate with Lear's emotional turbulence. This kind of metrical torsion, however we may analyse it in specific instances, is characteristic of Shakespeare in his later period. Our aim as readers is not to 'solve' the line to an imagined answer, but to discover more or less plausible possibilities within the parameters of normal pronunciation (we cannot, for example, wrench an accent from its normal syllable, except when singing, where such effects are regarded as acceptable). We can pause to note, too, the importance of elements off the page: the timbre of the actor's voice, intonation, facial expression, gesture, all of which contribute vitally to our perception of the moment of these lines.

This brief outline will, I hope, provide a useful starting point for accurate metrical analysis. Prosody is not exclusively for the examination regular verse: so-called free verse will still have a carefully considered rhythmic organisation, even if it does not fit any established regular metrical form.

Considerations

When analysing metre, we can bring questions such as these to bear:

What is the basic rhythm? Where is it varied, and why? Do variations point the meaning, eg by highlighting a contrast (YOU did, not ME) or imitating the sense in some way? We should not feel compelled to harness metrical and other sound effects to an interpretation of meaning: they can be aesthetic and sensual rather than semantic in significance, creating a pattern which is decorous, balanced, symmetrical, harmonious - or spiky, jerky and nervy. Dryden would give us examples of the first, Hopkins of the second (with exceptions either way), and in both cases the acoustic properties of the verse constitute a subverbal realm which we register even if we cannot interpret it in lexical terms (we feel it, but cannot put it into words, since it is beyond words). Metre is inextricably linked to syntax, punctuation and other devices, and is to be considered as part of a total cast of effects rather than as a single actor alone on the stage. Metre will be part of the voice of the poem solemn, stately, lively, boisterous, a voice frequently moved by some internal tension, exploratory, self-dramatising. The study of metre is at the very least a reminder that poetry is written primarily for the ear, rooted in spells, chants and incantations. The technicalities of the jargon in the end return us to the pre-verbal and mysterious origins of poetry, which remain as trace elements in even its most modern printed form.

Further Reading

Online

Amittai F Aviram,

Meter in English Verse

Cambridge English Faculty,

Virtual Glossary of Literary Terms

Series of articles by

Tina Blue

Books

James Fenton,

An Introduction to English Poetry

Paul Fussell,

Poetic Meter and Poetic Form

Stephen Fry,

The Ode Less Travelled

John Hollander,

Rhyme's Reason - a simultaneously entertaining and instructive book which explains forms by demonstrating them.

Andreas Petzold, Romanesque Art is attractive, authoritative, readable. The emphasis here is on how the art worked within the society, so there are chapters on patronage, women, the Church, other cultures (Classical, Jewish, Islamic). Not much extended object-specific analysis, but an excellent primer on looking for the significance of works you do encounter.

Andreas Petzold, Romanesque Art is attractive, authoritative, readable. The emphasis here is on how the art worked within the society, so there are chapters on patronage, women, the Church, other cultures (Classical, Jewish, Islamic). Not much extended object-specific analysis, but an excellent primer on looking for the significance of works you do encounter.

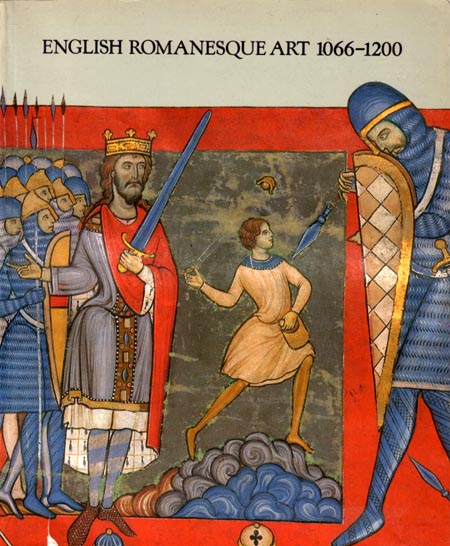

Zarnecki and other scholars produced English Romanesque Art 1066-1200, the catalogue which accompanied a major exhibition of Romanesque art from England, at the Hayward way back in 1984. All the arts are covered, and detailed descriptions of the exhibits make it a good source for getting to know particular works. Lots of information, perhaps best for occasional detailed reading.

Zarnecki and other scholars produced English Romanesque Art 1066-1200, the catalogue which accompanied a major exhibition of Romanesque art from England, at the Hayward way back in 1984. All the arts are covered, and detailed descriptions of the exhibits make it a good source for getting to know particular works. Lots of information, perhaps best for occasional detailed reading.