When you're set an essay, the natural and human reaction is to want to get it over with. But for high-stakes writing - for exams and such - this have-a-go approach is a bit risky. So it's hugely worthwhile to put some time aside to find a guide to the method of essay writing that clicks with you. Many websites offer help with this, and not a few offer to write them for you for a fee. After a brief trawl, the online resources below seemed to me particularly useful.

Here's a hub to various resources on all kinds of writings. I haven't looked at them all. The Creative Writing Resources looks very good. Open here.

For academic essays in particular, I recommend the Purdue University Online Writing Lab. Go to 'Common Writing Assignments' for detailed advice on argumentative essays etc. Breaks it down into stages.

Plenty of universities are posting their student guides online. Here's good one from Anglia Ruskin University.

Another good one is this, by David Gauntlett of the Institute of Communication Studies at Leeds. I like his examples of concision over waffle: Essay-Writing: The Essential Guide

Here's a very practical document by Tom Davis written for English undergraduates (but useful for other subjects), with some useful links of its own. Written in 2001 so the remarks on technology are a little archaic, but the advice on putting material into paragraphs is timeless. How to Write an Essay.

See also previous blog post, Guides to Good Writing.

Friday, 21 September 2012

Thursday, 20 September 2012

T S Eliot, Poems 1920

Surely the first thing that strikes anyone on looking at the selection from Poems, 1920 is that they are extraordinarily difficult. In 'Gerontion' and the quatrain poems, Eliot uses dislocation: we seem to slide suddenly from one scene, or voice, or topic, or image to another, and the link is not at all clear. Then there is the obstacle course of quotations and allusions - in 'Burbank' a whole heap of them - which defy us to recognise and make sense of them. On top of this are difficulties in language, such as the tortuous syntax of 'Gerontion', and the abstruse vocabulary ('Polypohiloprogenitive' etc.). As if that were not enough, we have strange names to makes sense of (Princess Volupine, the 'characters' in 'Gerontion'), references to classical myth ('Sweeney among the Nightingales') and obscure theology ('Mr Eliot's Sunday Morning Service'), and a lack of clear subject matter. And the voice with which the poems are delivered seems frequently to change in tone - from ironic and sardonic to philosophical to, occasionally, lyrical (the description of the painting in 'Mr Eliot's Sunday Morning Service'). It is comforting to discover that the best-read critics and scholars have found these poems

Surely the first thing that strikes anyone on looking at the selection from Poems, 1920 is that they are extraordinarily difficult. In 'Gerontion' and the quatrain poems, Eliot uses dislocation: we seem to slide suddenly from one scene, or voice, or topic, or image to another, and the link is not at all clear. Then there is the obstacle course of quotations and allusions - in 'Burbank' a whole heap of them - which defy us to recognise and make sense of them. On top of this are difficulties in language, such as the tortuous syntax of 'Gerontion', and the abstruse vocabulary ('Polypohiloprogenitive' etc.). As if that were not enough, we have strange names to makes sense of (Princess Volupine, the 'characters' in 'Gerontion'), references to classical myth ('Sweeney among the Nightingales') and obscure theology ('Mr Eliot's Sunday Morning Service'), and a lack of clear subject matter. And the voice with which the poems are delivered seems frequently to change in tone - from ironic and sardonic to philosophical to, occasionally, lyrical (the description of the painting in 'Mr Eliot's Sunday Morning Service'). It is comforting to discover that the best-read critics and scholars have found these poems extremely hard - even impossible - to fathom. Some have seen them as a bit of a dead end in Eliot's work (he never returned to this tight quatrain form for more than a few lines), an experimental phase between Prufrock and 'The Waste Land'.

Difficulty is itself an important aspect of Eliot's work, so we should pause and consider it. He himself took the view that modern poetry had to be complex if it was to present a truthful representation of modern experience. Here he is, in a lecture published in 1921:

It is not a permanent necessity that poets should be interested in philosophy, or in any other subject. We can only say that it appears likely that poets in our civilization, as it exists at present, must be difficult. Our civilization comprehends great variety and complexity, and this variety and complexity, playing upon a refined sensibility, must produce various and complex results. The poet must become more and more comprehensive, more allusive, more indirect, in order to force, to dislocate if necessary, language into his meaning. ('The Metaphysical Poets')

Why, we might ask following Eliot, should poetry be easy? Scientists don't expect the material world to deliver its secrets up easily; and if art is a comparable investigation into the human world of culture and civilization, then that, too is likely to be as dense and exacting as scientific research (Eliot compares the creative act to a scientific experiment in 'Tradition and the Individual Talent'). This is especially the case when that culture lies shattered into fragments after the cataclysm of World War One.

Here are some links to commentaries on the 1920 poems as a whole, and some of the individual poems.

Poems, 1920

Nigel Alderman, 'Where are the eagles and the trumpets?': the strange case of Eliot's missing quatrains - on the quatrain poems as a group. Accessible from JSTOR here.

Heather Bryant Jordan, Ara vos Prec: A Rescued Volume

Individual Poems

Critical interpretations of Gerontion

Thomas Day, analysis of 'Gerontion' in agenda poetry

Skylar Hamel, essay on The Hippopotamus

Cummings Guide, Sweeney Among the Nightingales

Gabriel Ellsworth, Analysis of 'Mr Eliot's Sunday Morning Service'

Keith Sagar, link on this page to Sagar's paper on 'Prufrock Supine and Sweeney Erect'

Labels:

Eliot (T S),

English Literature,

Modernism,

Poetry

Moissac Tympanum

|

| Image: Web Gallery of Art |

Superb images and brief text on paradoxplace

Andrew Tallon of Vassar College has produced some outstanding photographic resources, enabling the viewer to zoom in on details. See the bottom of his homepage.

A video of the Moissac portal led me to this wonderful blog on the Romanesque sculpture and architecture of the route to Santiago, The Joining of Heaven and Earth

Moissac is included in a useful chapter on Romanesque in the online World History of Art

Meyer Schapiro wrote a detailed study of the Moissac sculptures for his 1935 doctoral thesis. This work is available in two articles on JSTOR: 'The Romanesque sculpture of Moissac, Part I (1)' deals with the programme of capital sculptures in the cloister. The tympanum is described in detail in the second article, 'The Romanesque Sculpture of Moissac, Part 1 (II)'. Both can be conveniently read in book form in Meyer Schapiro and David Finn (photos), The Romanesque Sculpture of Moissac (1985). Schapiro's Charles Eliot Norton lectures on various sites are published as Meyer Schapiro, Romanesque architectural sculpture (2006).

Learning Architecture Terminology

Learning about architecture involves absorbing a fair few technical terms. As with identifying trees - my present hobby - the best thing is to go round looking at real buildings with a handbook and try out the naming of parts. Here are some recommendations.

Matthew Rice, Rice's Architectural Primer. This is the one I'd start with. Really helpful watercolour drawings which clarify parts of buildings and the different styles. If you're interested in domestic architecture (which tends to get overlooked in academic courses) then his Village Buildings of Britain is another treat.

Glossaries

It's always handy to have a glossary and / or illustrated history to turn to. A handsome printed one is: Owens Hopkins, Reading Architecture. I also consult Lever and Harris, Illustrated Dictionary of Architecture 800-1914. Though the title doesn't say so, this covers English architecture exclusively. It's well worth tracking down a second-hand copy. For a richly illustrated tour through Western buildings, an excellent book is Doreen Yarwood, A Chronology of Western Architecture.

Here are two (of many) online glossaries. You could try drip-feeding yourself on a term a day from these:

Buffalo Illustrated Architecture Dictionary

Roberta Barresi, Architecture Glossary

Classical

Learning the classical language - columns, orders and so forth - is a logical first move in studying Western architectural history. A classic, and handily short, text is John Summerson, The Classical Language of Architecture. This helps you not just to name the elments of buildings, but to think about their effects. A useful accompaniment is this online Glossary of Classical Architecture. The Looking at Buildings site has plenty of clear explanation.

Churches

Studying architecture in the West involves looking at an awful lot of churches, so it's a good idea to have something that focusses on this: Mcnamara and Tilney, How to Read Churches is very well illustrated. Matthew Rice has one coming out next year, which I'm sure will be excellent: Rice's Church Primer

Matthew Rice, Rice's Architectural Primer. This is the one I'd start with. Really helpful watercolour drawings which clarify parts of buildings and the different styles. If you're interested in domestic architecture (which tends to get overlooked in academic courses) then his Village Buildings of Britain is another treat.

Glossaries

It's always handy to have a glossary and / or illustrated history to turn to. A handsome printed one is: Owens Hopkins, Reading Architecture. I also consult Lever and Harris, Illustrated Dictionary of Architecture 800-1914. Though the title doesn't say so, this covers English architecture exclusively. It's well worth tracking down a second-hand copy. For a richly illustrated tour through Western buildings, an excellent book is Doreen Yarwood, A Chronology of Western Architecture.

Here are two (of many) online glossaries. You could try drip-feeding yourself on a term a day from these:

Buffalo Illustrated Architecture Dictionary

Roberta Barresi, Architecture Glossary

Classical

Learning the classical language - columns, orders and so forth - is a logical first move in studying Western architectural history. A classic, and handily short, text is John Summerson, The Classical Language of Architecture. This helps you not just to name the elments of buildings, but to think about their effects. A useful accompaniment is this online Glossary of Classical Architecture. The Looking at Buildings site has plenty of clear explanation.

Churches

Studying architecture in the West involves looking at an awful lot of churches, so it's a good idea to have something that focusses on this: Mcnamara and Tilney, How to Read Churches is very well illustrated. Matthew Rice has one coming out next year, which I'm sure will be excellent: Rice's Church Primer

Labels:

Architecture

Saturday, 8 September 2012

Rhetoric: Some Tropes

Accompanying another post on rhetorical schemes, here is one on tropes. Where schemes deal with sentences - clauses in parallel, etc. - tropes concern the artful deviation of words from their ordinary sense. In practice, the distinction between schemes and tropes can become artificial, as there is a natural symbiosis between word and syntax. Some figures (ie zeugma) have been classified variously as scheme and trope. There are also problems in talking about the 'ordinary' use of language. There are good arguments (see Owen Barfield's wonderful book Poetic Diction) that language in its normal state is metaphorically rich, and we have to make a special effort to reduce a word ro statement to carry single precise meanings: think of the work lawyers have to do to create documents that admit of only one interpretation - it suggests they might be working against the grain of the material of language.

Metaphor and Simile

Metaphor

Twisting a word from its usual sense to create another idea. Used to form striking comparisons between two unlike things to show something they still have in common. A metaphor can occur in various parts of speech, and it does not have to take the form a=b. There's a beautiful discussion of metaphor in the film Il Postino.

This book is a monument.

The sun blessed the bright sky. The sun shouted in the laughing sky.

That news just burns me up.

I stood in the lonely field [so-called transferred epithet, where the adjective describing me - lonely - is transferred to the field. Also an instance of Ruskin's pathetic fallacy, the fallacy being to suppose that inanimate things like fields have feeling (pathos) like loneliness.]

Simile

Also a comparison between two unlike things, made explicit by a word such as 'as' or 'like'

My love is like a red, red rose.

The silence settled like snow.

He entered the room as subtly as a steam train.

Part and whole

Synecdoche

Part stands for whole; genus or adjunct suggest main idea.

A village of three hundred souls. ['soul' is a part, standing for the whole person]

Keep your vehicle roadworthy [Vehicle stands - probably - for car, a specific kind of vehicle

: genus for species]

Give us this day our daily bread [Bread for food: species for genus]

Many hands make light work.

You did this for the oldest of motives - silver [the material 'silver' stands for what is made from it]

Metonymy

Virtually the same as synecdoche. An attribute or suggestive word is used to imply what is really meant.

Let's go and buy a bottle or two for dinner.

The top brass are meeting now.

He lives by his pen.

I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat.

Puns

Other ages took puns more seriously than we do. Shakespeare's plays and other Renaissance dramas has a level of wordplay that can seem puzzling to a modern audience. One way of looking at a line like Hamlet's punning 'A little more than kin and less than kind' is that it contains metaphor at its most compressed - several meanings in just one word (kind implies a comparison with 'kinned' (family-related) and 'kind' meaning species).

Antanaclasis

Word repeated in two different senses.

I want to scotch the idea that all the Scotch like Scotch.

Let's hang around while they hang Danny.

We make the traveller's lot a lot easier.

Paronomasia

Use words that sound the same but have different meanings. this is the groan groan type of pun.

I wish my parents would leave me a loan.

If you try the high stile you might look silly.

Let's have the fool for pudding.

Syllepsis

One word (usually a verb) governs two or mroe other words, though it is understood differently in each case. See zeugma, from which it is practically indistinguishable.

I take my hat and my leave.

Or stain her honour, or her new brocade.

... Dost sometimes counsel take - and sometimes tea.

His speech raised a laugh or two but also some hackles.

Figures of Substitution

Anthimeria

Substitute one part of speech for another. Several examples in late Shakespeare.

The thunder would not peace at my bidding. (noun for verb)

Lord Angelo dukes it well.

Knee thy way into his mercy.

I am going in search of the great perhaps (adverb for noun)

He wants to do the impossible (adjective for noun)

The fair, the chaste, the unexpressive she.

Periphrasis

Substitute a descriptive word or phrase for a name (eg a nickname); substitute a proper name for a quality associated with it.

Meet the mad jackal, captain of our village cricket team.

I am taught biology by the great fungus.

I like drawing, but I'm no Leonardo.

You'd need a Hercules to shift this lot.

Personification

Give abstract concepts or inanimate objects human qualities.

The ground is thirsty.

Smoke caressed the garden fence.

Fortune is cruel and arbitrary.

Apostrophe

Address to an absent person or personified abstraction: Death be not proud, Oh cruel fortune! etc.

Hyperbole

Substitute an over-the-top phrase for the real idea, to achieve emphasis.

There were millions of people at the party.

When he's angry, he makes the walls shake.

He's the King of the village hall ping-pong table.

Litotes

Opposite of hyperbole. Deliberate understatement, emphasising the point by opposite means. It's most common form is witht he negative.

That's no mean task.

I'm slightly puzzled as to why you burned the house down.

It would be rather helpful if you could throw me a rope to stop me from drowning.

I admit it's somewhat unusual to see a tree growing in someone's living room.

einstein was not unintelligent.

Rhetorical question (erotema)

Asking a question in order to make a point rather than to elicit an answer.

How many times do I have to tell you?

Isn't it odd that the murders only started after the new vicar was installed?

Irony

Using a word to signify the opposite of what it usually means. In its strong form it becomes sarcasm.

So you completely ignored the question - that was clever.

It's a privilege to be able to teach Wykehamists.

I can't wait to get the next gas bill.

Onomatopoeia

The sound of a word seems to underline its sense. Often combined with alliteration and assonance.

First march the heavy Mules, securely slow,

O'er hills, o'er Dales, o'er crags, o'er rocks they go

Jumping high o'er the shrubs of the rough ground,

Rattle the clatt'ring Cars, and the shockt Axles bound. (Pope, Iliad, 23:138-41)

Oxymoron

Joining together two words with different senses, to create a kind of self-contradiction.

Dry ice, conspicuously absent, deafening silence, cruel kindness, laborious leisure, the living dead

O miserable abundance, O beggarly riches.

Recommended Reading

Arthur Quinn and Barney R Quinn, Figures of Speech: 60 Ways to Turn a Phrase

Richard A Lanham, A Handlist of Rhetorical Terms

Online

Two handy lists:

Robert A Harris, A Handbook of Rhetorical Devices

University of Kentucky, Glossary of Rhetorical Terms

More comprehensive treatment:

Gideon Young, Silva Rhetoricae

Metaphor and Simile

Metaphor

Twisting a word from its usual sense to create another idea. Used to form striking comparisons between two unlike things to show something they still have in common. A metaphor can occur in various parts of speech, and it does not have to take the form a=b. There's a beautiful discussion of metaphor in the film Il Postino.

This book is a monument.

The sun blessed the bright sky. The sun shouted in the laughing sky.

That news just burns me up.

I stood in the lonely field [so-called transferred epithet, where the adjective describing me - lonely - is transferred to the field. Also an instance of Ruskin's pathetic fallacy, the fallacy being to suppose that inanimate things like fields have feeling (pathos) like loneliness.]

Simile

Also a comparison between two unlike things, made explicit by a word such as 'as' or 'like'

My love is like a red, red rose.

The silence settled like snow.

He entered the room as subtly as a steam train.

Part and whole

Synecdoche

Part stands for whole; genus or adjunct suggest main idea.

A village of three hundred souls. ['soul' is a part, standing for the whole person]

Keep your vehicle roadworthy [Vehicle stands - probably - for car, a specific kind of vehicle

: genus for species]

Give us this day our daily bread [Bread for food: species for genus]

Many hands make light work.

You did this for the oldest of motives - silver [the material 'silver' stands for what is made from it]

Metonymy

Virtually the same as synecdoche. An attribute or suggestive word is used to imply what is really meant.

Let's go and buy a bottle or two for dinner.

The top brass are meeting now.

He lives by his pen.

I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat.

Puns

Other ages took puns more seriously than we do. Shakespeare's plays and other Renaissance dramas has a level of wordplay that can seem puzzling to a modern audience. One way of looking at a line like Hamlet's punning 'A little more than kin and less than kind' is that it contains metaphor at its most compressed - several meanings in just one word (kind implies a comparison with 'kinned' (family-related) and 'kind' meaning species).

Antanaclasis

Word repeated in two different senses.

I want to scotch the idea that all the Scotch like Scotch.

Let's hang around while they hang Danny.

We make the traveller's lot a lot easier.

Paronomasia

Use words that sound the same but have different meanings. this is the groan groan type of pun.

I wish my parents would leave me a loan.

If you try the high stile you might look silly.

Let's have the fool for pudding.

Syllepsis

One word (usually a verb) governs two or mroe other words, though it is understood differently in each case. See zeugma, from which it is practically indistinguishable.

I take my hat and my leave.

Or stain her honour, or her new brocade.

... Dost sometimes counsel take - and sometimes tea.

His speech raised a laugh or two but also some hackles.

Figures of Substitution

Anthimeria

Substitute one part of speech for another. Several examples in late Shakespeare.

The thunder would not peace at my bidding. (noun for verb)

Lord Angelo dukes it well.

Knee thy way into his mercy.

I am going in search of the great perhaps (adverb for noun)

He wants to do the impossible (adjective for noun)

The fair, the chaste, the unexpressive she.

Periphrasis

Substitute a descriptive word or phrase for a name (eg a nickname); substitute a proper name for a quality associated with it.

Meet the mad jackal, captain of our village cricket team.

I am taught biology by the great fungus.

I like drawing, but I'm no Leonardo.

You'd need a Hercules to shift this lot.

Personification

Give abstract concepts or inanimate objects human qualities.

The ground is thirsty.

Smoke caressed the garden fence.

Fortune is cruel and arbitrary.

Apostrophe

Address to an absent person or personified abstraction: Death be not proud, Oh cruel fortune! etc.

Hyperbole

Substitute an over-the-top phrase for the real idea, to achieve emphasis.

There were millions of people at the party.

When he's angry, he makes the walls shake.

He's the King of the village hall ping-pong table.

Litotes

Opposite of hyperbole. Deliberate understatement, emphasising the point by opposite means. It's most common form is witht he negative.

That's no mean task.

I'm slightly puzzled as to why you burned the house down.

It would be rather helpful if you could throw me a rope to stop me from drowning.

I admit it's somewhat unusual to see a tree growing in someone's living room.

einstein was not unintelligent.

Rhetorical question (erotema)

Asking a question in order to make a point rather than to elicit an answer.

How many times do I have to tell you?

Isn't it odd that the murders only started after the new vicar was installed?

Irony

Using a word to signify the opposite of what it usually means. In its strong form it becomes sarcasm.

So you completely ignored the question - that was clever.

It's a privilege to be able to teach Wykehamists.

I can't wait to get the next gas bill.

Onomatopoeia

The sound of a word seems to underline its sense. Often combined with alliteration and assonance.

First march the heavy Mules, securely slow,

O'er hills, o'er Dales, o'er crags, o'er rocks they go

Jumping high o'er the shrubs of the rough ground,

Rattle the clatt'ring Cars, and the shockt Axles bound. (Pope, Iliad, 23:138-41)

Oxymoron

Joining together two words with different senses, to create a kind of self-contradiction.

Dry ice, conspicuously absent, deafening silence, cruel kindness, laborious leisure, the living dead

O miserable abundance, O beggarly riches.

Recommended Reading

Arthur Quinn and Barney R Quinn, Figures of Speech: 60 Ways to Turn a Phrase

Richard A Lanham, A Handlist of Rhetorical Terms

Online

Two handy lists:

Robert A Harris, A Handbook of Rhetorical Devices

University of Kentucky, Glossary of Rhetorical Terms

More comprehensive treatment:

Gideon Young, Silva Rhetoricae

Rhetoric: Examples of Schemes

Rhetoric: the art of persuasive speech. Or perhaps we might say, the art of expressive speech, in which language is shaped, 'figured', into configurations that compel our attention. Of the hundreds of figures of speech listed in reference works, only a few (metaphor, simile, alliteration) are in regular use in literary study. Here is a list of a few others: getting acquainted with them can certainly sharpen our sense of form in writing, and that perception of form can in turn - on a good day - help us to get a precise idea of the nature of the thought being expressed, and how its formal contours give it a rhythm and emotional current.

Rhetorical figures can be divided into schemes and tropes. Put simply, schemes deal with the shape of a sentence, tropes with the use of individual words. Schemes themselves can be subdivided, as follows:

Schemes of Balance

Parallelism Words, phrases or clauses with a similar structure:

Government of the people, by the people, for the people

I watched television and my wife read a book [Two clauses around and: the structure of each clause is Pronoun + transitive verb + object]

Players who abuse the opposition or maim the referee will not be selected in future. [Sentence includes two parallel phrases: abuse the opposition, maim the referee, both transitive verb + object]

Parallelism can convey the effect of being composed, in mind and speech, poised, in charge of one's material. Notice the various parallel phrases and clauses in the opening of Burke's Thoughts on the Cause of the Present Discontents:

It is an undertaking of some degree of delicacy to examine into the cause of public disorders. If a man happens not to succeed in such an enquiry, he will be thought weak and visionary; if he touches the true grievance, there is a danger that he may come near to persons of weight and consequence, who will rather be exasperated at the discovery of their errors, than thankful for the occasion of correcting them. If he should be obliged to blame the favourites of the people, he will be considered as the tool of power; if he censures those in power, he will be looked on as an instrument of faction.

One way of making clear the parts of text working in parallel is to place them in a column, to see how the elements of speech map onto each other:

If a man happens not to succeed

If he touches [If + subject + verb / verbal phrase

weak and visionary

weight and consequence [Two terms bound as a couplet, a pair of adjectives and a pair of nouns. Notice that in both pairs, a short Anglo-Saxon word is followed by a longer Latinate one]

exasperated at the discovery

thankful for the occasion [adj + preposition + noun]

And the last sentence (or period, as Burke might have considered it) consists of two balanced sentences (If clause, main clause), themselves pivoted on a semi-colon and containing parallel constructions (the tool of power / an instrument of faction)

Isocolon

When the parallelism is exact:

The louder he talked of his honour, the faster we counted our spoons.

To our right is the hard road to virtue, on our left lies the pretty path to perdition.

Antithesis

Contrasting ideas, whose relation is pointed by their position in parallel structures:

The fool thinks he is clever; the wise man knows he is ignorant.

That's one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.

Schemes of Unusual Word Order (Hyperbaton)

Anastrophe

Inversion of usual word order:

Slowly flows the stream

Those I fight I do not hate, those I defend I do not love.

Parenthesis

Start a sentence, then interrupt its natural flow with something else, even a complete sentence:

This crime - and I use this word deliberately - must be punished.

When he is angry - something which I am sorry to say occurs quite often - he loses all sense of proportion.

Apposition

Two things side by side, one explaining or modifying the other. (In Latin, of course, they can be some way from each other)

Ted, the village postman, has just been arrested. ['the village postman' is in apposition to 'Ted' - it saves using the relative clause ' who is the village postman']

Schemes of Omission

Ellipsis

Missing out a word or words which the reader has to 'fill in' from context.

I must to England [Obviously, 'I must go' is intended]

If you want a harder essay title, fine.

Idleness is the main vice of the young, wasted effort of the middle-aged, and despair of the old.

Asyndeton

Missing conjunctions between successive clauses.

I came, I saw, I conquered.

You were warned. You ignored this warning. You must be punished.

The teams went onto the field, the referee blew his whistle. The game had begun.

Polysyndeton

Opposite of asyndeton: lots of conjunctions.

And God said, Let there be light. And there was light. And God saw the light, that it was good.

It was cold and dark and silent and suddenly we felt very scared.

I entered the room although it was dark and atood very still but heard nothing.

Schemes of Repetition

Alliteration

Repeated initial or medial consonants. A useful sound effect:

Bruised and bloody, but not beaten.

A lovely, long, lazy summer afternoon.

Assonance

Repeated vowel sounds in stressed words, surrounded by different consonants.

An old, mad, blind, despised and dying king. [It's the 'i' sound in blind that gets repeated here]

Sing with a voice of joy.

The hard, dark path.

Anaphora

Starting successive clauses with the same word or words.

We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills.

Epistrophe

Ending successive clauses with the same word or words.

I don't like cricket. I don't play cricket. I don't want to hear another word about cricket.

Epanalepsis

Same word at beginning and end.

Blood will have blood.

Year chases year, decay pursues decay.

Anadiplosis

End a clause with a word, and begin the next clause with the same word.

Cars have parts, parts need repairs, and repairs are expensive.

Climax

Words, phrases or clauses arranged in order of increasing importance.

I serve my employer, my family, my country and my God.

Antimetabole

An ABBA structure where words are repeated in inverse order.

Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country.

Chiasmus

ABBA structure where grammatical structures or parts of speech are repeated inversely.

We proceeded at night, and by day we slept.

It's easy to make friends; to lose them is difficult.

Another post will give a list of tropes and reading recommendations.

Rhetorical figures can be divided into schemes and tropes. Put simply, schemes deal with the shape of a sentence, tropes with the use of individual words. Schemes themselves can be subdivided, as follows:

Schemes of Balance

Parallelism Words, phrases or clauses with a similar structure:

Government of the people, by the people, for the people

I watched television and my wife read a book [Two clauses around and: the structure of each clause is Pronoun + transitive verb + object]

Players who abuse the opposition or maim the referee will not be selected in future. [Sentence includes two parallel phrases: abuse the opposition, maim the referee, both transitive verb + object]

Parallelism can convey the effect of being composed, in mind and speech, poised, in charge of one's material. Notice the various parallel phrases and clauses in the opening of Burke's Thoughts on the Cause of the Present Discontents:

It is an undertaking of some degree of delicacy to examine into the cause of public disorders. If a man happens not to succeed in such an enquiry, he will be thought weak and visionary; if he touches the true grievance, there is a danger that he may come near to persons of weight and consequence, who will rather be exasperated at the discovery of their errors, than thankful for the occasion of correcting them. If he should be obliged to blame the favourites of the people, he will be considered as the tool of power; if he censures those in power, he will be looked on as an instrument of faction.

One way of making clear the parts of text working in parallel is to place them in a column, to see how the elements of speech map onto each other:

If a man happens not to succeed

If he touches [If + subject + verb / verbal phrase

weak and visionary

weight and consequence [Two terms bound as a couplet, a pair of adjectives and a pair of nouns. Notice that in both pairs, a short Anglo-Saxon word is followed by a longer Latinate one]

exasperated at the discovery

thankful for the occasion [adj + preposition + noun]

And the last sentence (or period, as Burke might have considered it) consists of two balanced sentences (If clause, main clause), themselves pivoted on a semi-colon and containing parallel constructions (the tool of power / an instrument of faction)

Isocolon

When the parallelism is exact:

The louder he talked of his honour, the faster we counted our spoons.

To our right is the hard road to virtue, on our left lies the pretty path to perdition.

Antithesis

Contrasting ideas, whose relation is pointed by their position in parallel structures:

The fool thinks he is clever; the wise man knows he is ignorant.

That's one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.

Schemes of Unusual Word Order (Hyperbaton)

Anastrophe

Inversion of usual word order:

Slowly flows the stream

Those I fight I do not hate, those I defend I do not love.

Parenthesis

Start a sentence, then interrupt its natural flow with something else, even a complete sentence:

This crime - and I use this word deliberately - must be punished.

When he is angry - something which I am sorry to say occurs quite often - he loses all sense of proportion.

Apposition

Two things side by side, one explaining or modifying the other. (In Latin, of course, they can be some way from each other)

Ted, the village postman, has just been arrested. ['the village postman' is in apposition to 'Ted' - it saves using the relative clause ' who is the village postman']

Schemes of Omission

Ellipsis

Missing out a word or words which the reader has to 'fill in' from context.

I must to England [Obviously, 'I must go' is intended]

If you want a harder essay title, fine.

Idleness is the main vice of the young, wasted effort of the middle-aged, and despair of the old.

Asyndeton

Missing conjunctions between successive clauses.

I came, I saw, I conquered.

You were warned. You ignored this warning. You must be punished.

The teams went onto the field, the referee blew his whistle. The game had begun.

Polysyndeton

Opposite of asyndeton: lots of conjunctions.

And God said, Let there be light. And there was light. And God saw the light, that it was good.

It was cold and dark and silent and suddenly we felt very scared.

I entered the room although it was dark and atood very still but heard nothing.

Schemes of Repetition

Alliteration

Repeated initial or medial consonants. A useful sound effect:

Bruised and bloody, but not beaten.

A lovely, long, lazy summer afternoon.

Assonance

Repeated vowel sounds in stressed words, surrounded by different consonants.

An old, mad, blind, despised and dying king. [It's the 'i' sound in blind that gets repeated here]

Sing with a voice of joy.

The hard, dark path.

Anaphora

Starting successive clauses with the same word or words.

We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills.

Epistrophe

Ending successive clauses with the same word or words.

I don't like cricket. I don't play cricket. I don't want to hear another word about cricket.

Epanalepsis

Same word at beginning and end.

Blood will have blood.

Year chases year, decay pursues decay.

Anadiplosis

End a clause with a word, and begin the next clause with the same word.

Cars have parts, parts need repairs, and repairs are expensive.

Climax

Words, phrases or clauses arranged in order of increasing importance.

I serve my employer, my family, my country and my God.

Antimetabole

An ABBA structure where words are repeated in inverse order.

Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country.

Chiasmus

ABBA structure where grammatical structures or parts of speech are repeated inversely.

We proceeded at night, and by day we slept.

It's easy to make friends; to lose them is difficult.

Another post will give a list of tropes and reading recommendations.

Friday, 7 September 2012

St Catherine's Hill, Winchester, 5 September 2012

A brief slideshow comprising of pictorial notes on an instructive walk around St Catherine's Hill, under the auspices of the Hampshire Wildlife Trust. It was interesting to learn about plans for managing this area: various clumps of even-aged trees and bushes (especially ash and hawthorn) have grown to form canopies, which hampers biodiversity. It is hoped that a scheme of felling and thinning out these clumps will encourage more downland grasses and flowers to grow, and provide the mixed scrub which makes a better environment for birds, butterflies and other wildlife.

The HWT page on this wonderful nature reserve can be found here.

Labels:

countryside,

Natural History,

Trees,

walks,

wildflowers,

Winchester,

woodland

Thursday, 6 September 2012

Romanesque Altar of Sant Serni de Tavèrnoles

| ||

| Altar Frontal from St Serni de Tavèrnoles. Second half of 12th century. Tempera on wood. Image: Wikimedia.

This altar frontal, from a monastery, is different in several ways to other examples of the genre: instead of a hierarchical series, in which a central figure is flanked by lesser beings, we have a more democratic way of representing things. The figures are all the same size and occupy the same space. I like to see it as a procession - as if they are all walking in suitably stately fashion towards us, but flattened out, so we see two lines at either side of Saint Serni in the centre.

Sant Serni is better known by his French name of St Sernin or Saturnin. He was a martyred bishop of Toulouse, where he is honoured by the largest Romanesque church in Europe. The choice of image here is another unusual feature. Other representations show revolting pictures of the saint's martyrdom in the year 250: he refused to sacrifice to pagan deities, and was sentenced to be dragged by a maddened bull throught he city streets. But here he is surrounded by other bishops (note the mitres and croziers), and apparently presides over an episcopal assembly. To warm the hearts of bureaucrats everywhere, we have here a reverent image of the saint chairing a committee (the scrolls are the agenda, perhaps, or dreaded AOB). Anyway, everyone looks very calm and happy as the Saint blesses them, so the procession / meeting is probably nearing its close. The deep mellow colours add to this serene air.

It's a big piece, and it has been suggested that it might have served as a sarcophagus or reredos. But then the church it comes from is big too, and needed something on this scale to be the centre of processions.

It's interesting to compare the Barcelona Frontal with the much busier one dedicated to the same saint (under the name St Sadurní) in the Episcopal Museum of Vic, made in the twilight years of Romanesque:

Briefly, this shows Christ Pantocrator in the middle, surrounded by the Tetramorph. Top left: Saint Saturninus refuses to bow down to a pagan idol, in the form of a bull. Bottom left: he is dragged by a bull through the Capitol of Toulouse. Top right: the saint has just saved a bunch of people from drowning, and blesses them. The style is very different: Byzantine influence has led to smoother modelling of faces and bodies. This new Greek style was to become predominant in the thirteenth century. The source of all of this is the museum website entry, which you can read here.

Wikipedia entry on St Saturnin

Links to many images of St Saturnin from JISCMail

|

Romanesque Altar Frontal: Frontal d'Ix

This is the 'Frontal d'Ix', a painted (tempera) wooden (pine) altar frontal (fancy word for this: antependium) from the small Romanesque Church (single nave, round apse) dedicated to St Martin, in the village of La Guingeta d'Ix. It was made sometime around the middle of the twelfth century, and presently adorns the first room of the Romanesque galleries in MNAC. It's in fact one of the oldest pieces in that collection, having been given by a private collector in 1889 (the first exploratory trip to the Pyrennean churches was undertaken in 1907).

| St Martí, La Guingeta d'Ix. Wikimedia. |

The love of geometrical pattern and decoration is immediately apparent. It's interesting that the four sides around the iconographic images use different motifs. At the top there's a band of strikingly 3D-effect cubes, or interlocking zigzag straps, however you want to see them, picking up on the reds and blues in the middle. Going clockwise, we see vegetal motifs on the right, and at the bottom the so-called 'rinceaux' or foliage pattern. Up the left side, medallions, alternating vegetal and animal images. Behind them is a world of kells, mosaics, miniatures - the whole medieval vision of endless symmetrical patterns, stretching from Ireland to Byzantium.

Now to the subject matter, starting in the centre with the Maiestas Domini - the Majesty of the Lord, the motif of the Saviour enthroned. The figure is very similar to the one in the Seu d'Urgell frontal (see below): elongated face, long thin nose and wide-open eyes, beard and treatment of hair, and taches or red spots on cheeks and forehead all match up. The Christ of Ix does look rather less grim and more cheerful, though. He is seated at the intersection of two coloured circles, which make up the globe mandorla, a motif we can trace back to Carolingian times. He is wearing a red tunic, with a fringed blue mantle. Heavy linear folds following the logic of pattern rather than anatomy. Again, the nimbus bears a crucifer, which goes slightly over the edges and above the mandorla. Left hand rests on the Book, right hand raised in blessing. Unlike Urgell, this right hand is also carrying a small round object. Very likely it symbolises the world (some manuscripts helpfully name it, 'mundus'), but it could also be the Host (suitable to have the symbol of the Eucharist on an altar) - and I don't see why the interpreting viewer couldn't flip between these two significations. The Alpha and Omega letters remind us of the Saviour's rule over the beginning and end of the world. No tetramorph (as in Vézelay etc.) but a deep red background decorated with floral motifs - another similarity to the Seu d'Urgell frontal.

Now to the subject matter, starting in the centre with the Maiestas Domini - the Majesty of the Lord, the motif of the Saviour enthroned. The figure is very similar to the one in the Seu d'Urgell frontal (see below): elongated face, long thin nose and wide-open eyes, beard and treatment of hair, and taches or red spots on cheeks and forehead all match up. The Christ of Ix does look rather less grim and more cheerful, though. He is seated at the intersection of two coloured circles, which make up the globe mandorla, a motif we can trace back to Carolingian times. He is wearing a red tunic, with a fringed blue mantle. Heavy linear folds following the logic of pattern rather than anatomy. Again, the nimbus bears a crucifer, which goes slightly over the edges and above the mandorla. Left hand rests on the Book, right hand raised in blessing. Unlike Urgell, this right hand is also carrying a small round object. Very likely it symbolises the world (some manuscripts helpfully name it, 'mundus'), but it could also be the Host (suitable to have the symbol of the Eucharist on an altar) - and I don't see why the interpreting viewer couldn't flip between these two significations. The Alpha and Omega letters remind us of the Saviour's rule over the beginning and end of the world. No tetramorph (as in Vézelay etc.) but a deep red background decorated with floral motifs - another similarity to the Seu d'Urgell frontal. Now we can look at the sides, starting with the right. The equivalent space in the Seu d'Urgell frontal is a single plane, but here it is divided into four frames, each containing two figures. We can spot St Peter at once with his gigantic key (I like the way this breaks out of his space into the frame, forming a parallel with the two blessing hands and the codex if we read across to the left). Next frame along in the top row is St Martin, in his iconic act of dividing his robe with a beggar. This scene has the scholars vexed, though: St Martin (of Tours) is usually shown on horseback when he does this, not standing; the 'beggar' doesn't exactly look in need of more wardrobe here; and the staff linked to a chain over his right shoulder suggests he is a captive, which points to stories in other saints' lives but not St Martin. A conflation of some kind? The precise coherence of the elements seems to have become obscured by time. Also obscure, if they were ever known, are the identities of any of the other figures. They are obviously apostles, but who is who seems to be anyone's guess. As with the Urgell frontal, they all look towards Christ (though not with the same pronounced tilt); again, they're differentiated by being bearded and beardless, and have the same rather block-like faces. Notice too the pearl-like decoration around the edges.

Now we can look at the sides, starting with the right. The equivalent space in the Seu d'Urgell frontal is a single plane, but here it is divided into four frames, each containing two figures. We can spot St Peter at once with his gigantic key (I like the way this breaks out of his space into the frame, forming a parallel with the two blessing hands and the codex if we read across to the left). Next frame along in the top row is St Martin, in his iconic act of dividing his robe with a beggar. This scene has the scholars vexed, though: St Martin (of Tours) is usually shown on horseback when he does this, not standing; the 'beggar' doesn't exactly look in need of more wardrobe here; and the staff linked to a chain over his right shoulder suggests he is a captive, which points to stories in other saints' lives but not St Martin. A conflation of some kind? The precise coherence of the elements seems to have become obscured by time. Also obscure, if they were ever known, are the identities of any of the other figures. They are obviously apostles, but who is who seems to be anyone's guess. As with the Urgell frontal, they all look towards Christ (though not with the same pronounced tilt); again, they're differentiated by being bearded and beardless, and have the same rather block-like faces. Notice too the pearl-like decoration around the edges. The left side has the same four images. Second from the right on the top is St Martin again. No mysteries here - he is clearly depicted as a bishop with a crozier. I take it that what looks like a sore spot on his crown is the tonsure - the same detail distinguishes St Peter in the Urgell piece. And he gets his name in red letters, to the left of his halo. All the other figures are anonymous apostles. One detail I find oddly delightful is that St Martin is the only one in the whole work wearing shoes! The separate scenes are unified by the geometrical format, underlined by the simple alternation of red and yellow backgrounds. across the middle is an inscription - partial erasure, intricate letter decoration and shorthand abbreviations make it a challenge, but it has been deciophered as 'Sol et Lux Sanctorum Maneo in Praeclara Honorum' which I think means something like 'I dwell in the bright sun and the light of the beautiful saints' but gentle correction welcomed.

The left side has the same four images. Second from the right on the top is St Martin again. No mysteries here - he is clearly depicted as a bishop with a crozier. I take it that what looks like a sore spot on his crown is the tonsure - the same detail distinguishes St Peter in the Urgell piece. And he gets his name in red letters, to the left of his halo. All the other figures are anonymous apostles. One detail I find oddly delightful is that St Martin is the only one in the whole work wearing shoes! The separate scenes are unified by the geometrical format, underlined by the simple alternation of red and yellow backgrounds. across the middle is an inscription - partial erasure, intricate letter decoration and shorthand abbreviations make it a challenge, but it has been deciophered as 'Sol et Lux Sanctorum Maneo in Praeclara Honorum' which I think means something like 'I dwell in the bright sun and the light of the beautiful saints' but gentle correction welcomed.There's a strong feeling among experts that this Frontal and the one from Seu d'Urgell came from the same workshop. Parallels to many of the motifs have been found in manuscripts, and there are close similarities to sculptures in the monastery of Ripoll. These details are explored in humbling detail by Walter Cook in his 1923 article. Cook didn't have absolutely all the details to hand when he wrote, as the provenance of the piece only came to light in 1944 - but the article is a model of detailed description and iconographic research.

|

| Seu d'Urgell Frontal |

Sources.

Mostly plundered from the Catalan Viquipedia entry

The Earliest Painted Panels of Catalonia (II)

Walter W. S. Cook, 'The Earliest Painted Panels of Catalonia (II)', The Art Bulletin , Vol. 6, No. 2 (Dec., 1923), pp. 31-60 (especially 32-38).

Blog entry on Seu d'Urgell Frontal

Blog entry on Seu d'Urgell Frontal

Romanesque Altar Frontal from Seu d'Urgell

Another wonderful Romanesque altar frontal in MNAC, showing Christ surrounded by the apostles. Dated about 1150, tempera on wood. From a church in the old dicese of Urgell. Heavy linearity and symmetry (look at the feet!) tending - physical details like garments and bodies all become the occasion for abstract patterning, as if the pattern is the reality, and the physical object just a brief configuration as the play of line and colour goes on for ever. This play, or pull, between concrete and abstract gives much of Romanesque art itrs animating tension. I like the tilted heads - impossible not to follow the gaze from side to centre.

Video introduction produced by MNAC:

Short entry on Spain is Culture

Wikipedia entry (note: 'lack of funds' in the description is a mistranslation and should read 'lack of background')

Article: Walter W. S. Cook, 'The Earliest Painted Panels of Catalonia (II)', The Art Bulletin, Vol. 6, No. 2 (Dec, 1923), pp. 31-60 on JSTOR. Article begins with a detailed account of this frontal, pages 30-32. It's a great example of detailed visual description - how pausing, looking and putting into words what we see leads to a much sharper awareness of what is happening. The eye wants to skim - particularly in a musem where there is so much to see - so sketching or describing like this is an essential discipline for slowing down and focussing.

Some lovely illustrations, and a good section on Geometrical Forms, in MNAC's excellent Guia Visual Art Romanic.

Video introduction produced by MNAC:

Short entry on Spain is Culture

Wikipedia entry (note: 'lack of funds' in the description is a mistranslation and should read 'lack of background')

Article: Walter W. S. Cook, 'The Earliest Painted Panels of Catalonia (II)', The Art Bulletin, Vol. 6, No. 2 (Dec, 1923), pp. 31-60 on JSTOR. Article begins with a detailed account of this frontal, pages 30-32. It's a great example of detailed visual description - how pausing, looking and putting into words what we see leads to a much sharper awareness of what is happening. The eye wants to skim - particularly in a musem where there is so much to see - so sketching or describing like this is an essential discipline for slowing down and focussing.

Some lovely illustrations, and a good section on Geometrical Forms, in MNAC's excellent Guia Visual Art Romanic.

Wednesday, 25 July 2012

Gregorian Chant: Four Antiphons of the Virgin Mary

The last four melodies in Rutter's Eleven Gregorian Chants are Four Antiphons of the Virgin Mary, compositions from between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries which closed the office of Compline (the last Office of the day). An Antiphon is the root of 'Anthem' (Old English antefne), meaning a song of praise or devotion. The Marian antiphons are anthems sung to the Virgin Mary, using independent texts without psalms. Here are some links to Gregorian notation and performances. These Marian hymns can also be found gathered here.

Alma Redemptoris Mater

Written by Hermannus Contractus (Herman the Cripple, 1013-54). Like the others below, this is given int he longer version known as 'Solemn Tone'. Opening with a long melisma, this is sung at the Advent to Candlemas. There are some comments by musicologists and other information here.

Ave Regina caelorum (Candlemas to Holy Week). The Marian hymns were used as the basis for many arrangements in the Renaissance and later. There is a useful gathering here of some of these polyphonic versions.

Regina caeli laetare (Easter Even to Pentecost). See this site for different versions and performances.

Salve Regina

Sources and Further Reading

History and background to Marian Antiphons

Entry by Richard Taruskin from Oxford History of Western Music

Alma Redemptoris Mater

Written by Hermannus Contractus (Herman the Cripple, 1013-54). Like the others below, this is given int he longer version known as 'Solemn Tone'. Opening with a long melisma, this is sung at the Advent to Candlemas. There are some comments by musicologists and other information here.

Ave Regina caelorum (Candlemas to Holy Week). The Marian hymns were used as the basis for many arrangements in the Renaissance and later. There is a useful gathering here of some of these polyphonic versions.

Regina caeli laetare (Easter Even to Pentecost). See this site for different versions and performances.

Salve Regina

Sources and Further Reading

History and background to Marian Antiphons

Entry by Richard Taruskin from Oxford History of Western Music

Labels:

12th Century,

Early Music,

Gregorian Chant,

Music

Romanesque Art: Apse of St Pere d'Urgell

|

| Apse of St Pere, Seu d'Urgell. MNAC, Barcelona. Image: Wikimedia Commons. |

Subject The subject matter is, characteristically, a theophany - that is, a vision in which divine majesty is revealed. Christ appears in a mandorla (mystical almond shape), manifesting the Maiestas Domini (the Majesty of the Lord). Around him are the creatures making up the Tetramorph, the symbols of the Four Evangelists: to the right of the mandorla we see the eagle (St John) and the ox (St Luke). It is notable that Christ is standing, not enthroned - imagery which goes back to Early Christian models. This fact, together with the pleats of the drapery and the vertical elongation of the figure, have led some to suggest that the subject is the Ascension. But other elements of the iconography point to the Second Coming, when Christ returns at the end of the world to judge the living and the dead. We notice that Christ holds the Book of Life in his left hand, and has his right hand raised in blessing. Beneath the horizontal band, the fragmentary inscription comes from a Latin liturgical hymn concerning the Last Judgement.

On the lower level, Mary and the Apostles stand in pairs. They are identified in Latin shorthand (S Petus: Sanctus Petrus, S Iohs: Sanctus Johannis etc.) and by their attributes. From the left: St Andrew carrying the cross (on which he was crucified); St Peter with the keys to heaven; St Mary, holding a crown in her covered left hand (identifying her as the Queen of Heaven; the covered hand reminds me of the covered left hand of Justinian and attendants in the S Vitale Ravenna mosaic); St John holding his gospel with a similarly covered hand; on the right, we can just identify Paul from his name.

Style Romanesque art was formed from a diversity of stylistic influences, and we can see several of them here. The scene of Theophany itself derives from Early Christian art of late antiquity. Here, the modelling of the figures, and the loosely geometrical approach to the drapery, point to the art of Provence, which was strongly influenced by classical models. The white background of the upper part is characteristic of southern and central France, while a similar image has been identified in a manuscript from St Mary of Lagrasse, dated to the time of Abbot Robert (1086-1108). The lands of this community included Urgell in the eleventh and twelfth centuries.

Observations One of the striking features of this painting is the interlaced geometrical schemes, especially in the beautiful central band where the pattern gives an impression of depth: this takes us to another stylistic source, the geometrical art of the barbarians and the early Middle Ages (the Celtic patterns in the Book of Kells, for example). The love of pattern is shown in the mandorla, in the semicircular configuration where Christ's feet extend (he is either taking off or coming in to land), and around the window openings. The band around the central window, punctuating the white horizontal line of the inscription, helps to join the separate spaces (as the trumeau abuts the lintel at Moissac). Deep browns and reds give a unifying tone to the whole composition, while among the vivid colours we notice the blue of Mary's mantle, made from lapis lazuli. Faces are elongated and - by modern realist standards - inexpressive. Yet the large eyes, with their deep mirada fuerte, give them a compelling intensity; and the painter has clearly tried to differentiate them with different beards, hair colour etc. (We think of the row of elders on the lintel of the tympanum at Moissac - first apparently identical, but each given a distinctive posture). We notice the love of symmetry when we look across the pairs of figures beneath, and see the disposition of hands being mirrored. The bodies seem to face outward to the viewer, while feet and hands indicate they are turned slightly inwards towards each other: the pictorial plane is ambiguous. There is a blend of space and intricate detail, animation and stillness, creating the drama of theophany, the transcendence from the earthly to the spiritual realm.

Sources

Most of the above is derived from the Guia art romanic published by MNAC.

Wikipedia netry on St Miquel de la Seu d'Urgell

Further bibliography on Ars Picta

Labels:

12th Century,

Art,

Catalan Romanesque,

Catalonia,

Romanesque

Tuesday, 24 July 2012

Gregorian Chant: Victimae Paschalis laudes

Eleventh-century chant. Sequence sung on Easter Sunday. Attributed by some to Notker the Stammerer. Rutter, Eleven Gregorian Chants, p.8

Labels:

Early Music,

Gregorian Chant,

Music

Monday, 23 July 2012

St Vicenç, Cardona

This church is in the ‘First Romanesque’ style. The First Romanesque is a style of

building of roughly 950-1050, the first century of Romanesque. This was a period when builders were experimenting with

developing new forms and new solutions to the problems of vaulting and lighting

a church. The style is common to churches in the Mediterranean area from Lombardy to Catalonia, from which

it subsequently spread upwards to the regions of France. As well as being an example of this

particular style, St Vicenç in Cardona exemplifies some

of the key elements of Romanesque architecture: clearly organised space, with

the units marked out by architectural elements; stone vaulting; a Latin Cross

groundplan; the development of the East end with chapels projecting from

transepts; blind arches decorating the exterior; and a general sense of

restraint and fitness for purpose. As Eric Fernie puts it, “nothing is

superfluous, nothing confused” (entry on Romanesque architecture in Grove). Studying this church is thus a good

introduction to ‘reading’ Romanesque church architecture in general.

Location

Cardona is in the county of Bages, roughly in the centre of this map.

Interior Elevation

· Inside the Crossing Tower is a dome carried on

pendentives – a feature from Eastern architecture. Above that is the octagonal drum (cimborio).

History

A church is documented on the site from 980. Around 1019, it was redeveloped by the Viscount Bermon, who reformed a religious (Augustinian) community that was present there from the late tenth century. The present church was built beween c.1029 and 1040, when it

was consecrated by Eriball, the Bishop of Urgell .The church and community were under the

control of the lords of the castle of Cardona – a reminder of the close

association of Romanesque architectuyre and the feudal system. Typically of many Romanesque churches,

especially in Catalonia, it is dramatically situated on a rocky hilltop.

|

| Groundplan. Source: learn.columbia.edu |

Architecture

Groundplan:

· The church is compose of a wide nave and two narrower

aisles.

· Naves and aisle are crossed by a transept, which

is slightly wider, but not very long: it barely projects beyond the basic rectangular plan. Nave

crossed by transept gives the Latin Cross groundplan.

·

The East end is emphasised, with chapels

projecting from the North and South arms

of the transept, giving three semicircular apses.

Interior Elevation

|

| Interior elevation. Source: romanicocatalan.com |

· Barrel vaulting is used in the nave, with transverse arches clearly articulating three bays + crossing. Aisles have groin vaulting.

· The Tribune at the West forms a special gallery,

an elevated space for the noble family of the castle: this is a feature derived

from Carolingian architecture.

· The vaults are notably high (more than 19 metres), a characteristic feature of Catalan Romanesque churches, and also of Eastern derivation.

|

| Piers; shafts continue into transverse arches. Barrel vaults |

|

| Nave: shafts join the two storeys; raised Chancel |

|

| Transverse arches and groin vaults in aisles. |

|

| Dome inside Crossing Tower. On pendentives, with scallop shapes. |

·

Inside the Crossing Tower is a dome carried on

pendentives – a feature from Eastern architecture.

Exterior

·

The Crossing is marked by an octagonal tower.

· Blind arches create a regular rhythm and unify the parts of the building. The decoration is very restrained, consisting of

repeated shapes largely defined by straight lines.

· The three chapels are clearly legible in the

outward appearance of the East end.

Crypt

·

A three-aisled crypt with columns carrying

vaults from simple pyramidal capitals lies beneath the Chancel, which is raised above the level of the nave.

Features typical of Catalan Romanesque: Nave and two aisles;

high vaults; Latin Cross plan.

Features typical of Romanesque: articulation – clear division

of space (bays, aisles, transepts, apses all clearly defined by simple lines and arches); symmetry in plan; austere decoration.

Another example of the 'First Romanesque' is St Philibert, Tournus.

Sources

Text, photos, plan and video on romanicocatalan.com

Catalan Wikipedia entry

Excellent photos, with images of the original painted decorations (c.1200) now in MNAC, are on the Catalan Monastery site.

Fernie, Grove entry; Zarnecki, Romanesque; Focillon, Art of the West.

Gregorian Chant: Vexilla Regis, Pange Lingua, Adoro te devote

More Gregorian chants, following the selection in Rutter's Eleven Gregorian Chants.

Vexilla Regis

Text (and possible melody) by Venantius Fortunatus (c.530-c.600/609), who composed this hymn in 569 to celebrate a procession bringing a fragment of the True Cross to Poitiers. Unsurprisingly, it is concerned with the Cross and Christ's Passion; in the Church calendar, it is sung at Vespers in Passiontide (Holy Week). A selection of Venantius' poems can be found on the Latin Library, including the text below. More Venantius poems, with facing translation, are printed in Helen Waddell's Medieval Latin Lyrics (4th ed., 1933), 58-67.

Vexilla regis prodeunt

Vexilla regis prodeunt

Fulget crucis mysterium

Quo carne carnis conditor

Suspensus est patibulo.

Quo vulneratus insuper

Mucrone diro lanceae

Ut nos lavaret crimine

Manavit unda et sanguine.

Impleta sunt quae concinit

David fideli carmine

Dicens In nationibus

Regnavit a ligno Deus.

Arbor decora et fulgida

Ornata Regis purpura

Electa digno stipite

Tam sancta membra tangere.

Beata, cujus brachiis

Saecli pependit pretium

Statera facta corporis

Praedamque tulit tartari.

O Crux ave, spes unica

In hac triumphi gloria

Auge piis justitiam

Reisque dona veniam.

Te summa Deus Trinitas

Collaudet omnis spiritus:

Quos per crucis mysterium

Salvas, rege per saecula. Amen.

For text with Blount's 1717 translation, see here.

Text and literal translation here

Performance by Schola Gregoriana Mediolanensis

Text, video and Gregorian notation are given by the excellent Brasil-based gregoriano.org site

Two Hymns by Thomas Aquinas

Pange Lingua

Text written in 1263 by St Thomas Aquinas, to an earlier melody. Hymn sung at the Feast of Corpus Christi.

Adoro te Devote

Eucharistic Hymn.

Vexilla Regis

Text (and possible melody) by Venantius Fortunatus (c.530-c.600/609), who composed this hymn in 569 to celebrate a procession bringing a fragment of the True Cross to Poitiers. Unsurprisingly, it is concerned with the Cross and Christ's Passion; in the Church calendar, it is sung at Vespers in Passiontide (Holy Week). A selection of Venantius' poems can be found on the Latin Library, including the text below. More Venantius poems, with facing translation, are printed in Helen Waddell's Medieval Latin Lyrics (4th ed., 1933), 58-67.

Vexilla regis prodeunt

Vexilla regis prodeunt

Fulget crucis mysterium

Quo carne carnis conditor

Suspensus est patibulo.

Quo vulneratus insuper

Mucrone diro lanceae

Ut nos lavaret crimine

Manavit unda et sanguine.

Impleta sunt quae concinit

David fideli carmine

Dicens In nationibus

Regnavit a ligno Deus.

Arbor decora et fulgida

Ornata Regis purpura

Electa digno stipite

Tam sancta membra tangere.

Beata, cujus brachiis

Saecli pependit pretium

Statera facta corporis

Praedamque tulit tartari.

O Crux ave, spes unica

In hac triumphi gloria

Auge piis justitiam

Reisque dona veniam.

Te summa Deus Trinitas

Collaudet omnis spiritus:

Quos per crucis mysterium

Salvas, rege per saecula. Amen.

For text with Blount's 1717 translation, see here.

Text and literal translation here

Performance by Schola Gregoriana Mediolanensis

Text, video and Gregorian notation are given by the excellent Brasil-based gregoriano.org site

Two Hymns by Thomas Aquinas

Pange Lingua

Text written in 1263 by St Thomas Aquinas, to an earlier melody. Hymn sung at the Feast of Corpus Christi.

Adoro te Devote

Eucharistic Hymn.

Labels:

Early Music,

Gregorian Chant,

Music,

Religion

Saturday, 21 July 2012

Gregorian Chants: Hodie Christus Natus Est, Kyrie de Angelis, Veni Creator Spiritus

I have been enjoying geeting to know Eleven Gregorian Chants, edited (in modern notation) by John Rutter. Here are some notes and links to the first three chants in this publication, which may help in appreciating and, above all, singing them.

Hodie Christus Natus Est

Ad Magnificat, Antiphona, In II Vesperis In Nativitate Domini (Antiphonale Monasticum (1934)p.249; Liber Usualis (1961), p.413). Mode 1, Dorian (D to D on white notes, with the final, or home note D)

Hodie Christus natus est: Today Christ is born:

hodie Salvator apparuit: today the Saviour has appeared:

hodie in terra canunt angeli, today on earth the angels sing,

laetantur archangeli: the archangels rejoice:

hodie exsultant justi, today the righteous exult,

dicentes: saying:

Gloria in excelsis Deo, Glory to God in the highest

alleluia. alleluia.

Here is a beautiful rendition, with neumatic notation, by the Benedictine nuns of the Abbey of Notre Dame d'Argentan.

Kyrie VIII (de Angelis)

This is the opening of the Missa de Angelis, from the 15th / 16th century. Note the extended melismas (one syllable sung across many notes). Mode VIII (Hypomixolydian: 'Mixolydian', a so-called authentic mode has the scale dewscribed by G to G, with D as the dominant; Hypo- indicates a 'plagal' mode, ie an even-numbered mode lying 'beneath' the authentic. Hypo-mixolydian has the same final as Mixolydian (G) but runs from domiannt to dominant (D to D).

Solo voice:

Other performances:

Monks of Santo Domingo de Silos (organ accompaniment)

Veni Creator Spiritus

This is one of the great hymnns of the Western Church, attributed to Rabanus Maurus in the 9th century, and in general use by the 12th century. It is sung at the Feast of Pentecost, and at important ceremonies such as Ordination. (Mode VIII)

A splendid blog entry by Clerk of Oxenford gives links to various performances and an interesting account of various translations.

For Gregorian notation, Latin text with literal English translation, see Chants of the Church (pdf text, p.175)

Unaccompanied:

Accompanied:

Hodie Christus Natus Est

Ad Magnificat, Antiphona, In II Vesperis In Nativitate Domini (Antiphonale Monasticum (1934)p.249; Liber Usualis (1961), p.413). Mode 1, Dorian (D to D on white notes, with the final, or home note D)

Hodie Christus natus est: Today Christ is born:

hodie Salvator apparuit: today the Saviour has appeared:

hodie in terra canunt angeli, today on earth the angels sing,

laetantur archangeli: the archangels rejoice:

hodie exsultant justi, today the righteous exult,

dicentes: saying:

Gloria in excelsis Deo, Glory to God in the highest

alleluia. alleluia.

Here is a beautiful rendition, with neumatic notation, by the Benedictine nuns of the Abbey of Notre Dame d'Argentan.

Kyrie VIII (de Angelis)

This is the opening of the Missa de Angelis, from the 15th / 16th century. Note the extended melismas (one syllable sung across many notes). Mode VIII (Hypomixolydian: 'Mixolydian', a so-called authentic mode has the scale dewscribed by G to G, with D as the dominant; Hypo- indicates a 'plagal' mode, ie an even-numbered mode lying 'beneath' the authentic. Hypo-mixolydian has the same final as Mixolydian (G) but runs from domiannt to dominant (D to D).

Solo voice:

Other performances:

Monks of Santo Domingo de Silos (organ accompaniment)

Veni Creator Spiritus

This is one of the great hymnns of the Western Church, attributed to Rabanus Maurus in the 9th century, and in general use by the 12th century. It is sung at the Feast of Pentecost, and at important ceremonies such as Ordination. (Mode VIII)

A splendid blog entry by Clerk of Oxenford gives links to various performances and an interesting account of various translations.

For Gregorian notation, Latin text with literal English translation, see Chants of the Church (pdf text, p.175)

Unaccompanied:

Accompanied:

Labels:

Early Music,

Gregorian Chant,

Music

Wednesday, 23 May 2012

Reading the Romanesque

In answer to a request, here are some suggestions for reading on Romanesque Art, conventionally dated to c.1000 to c.1200 with all sorts of blurring and overlapping at either end of course. Here are some one-stop-shop books which cover all the arts of the period. Specific books on architecture etc. can be left for other posts.

Anne Shaver-Crandell, Cambridge Introduction to Art: The Middle Ages is an excellent starting-point. Clear and helpful chapter on Romanesque.

Andreas Petzold, Romanesque Art is attractive, authoritative, readable. The emphasis here is on how the art worked within the society, so there are chapters on patronage, women, the Church, other cultures (Classical, Jewish, Islamic). Not much extended object-specific analysis, but an excellent primer on looking for the significance of works you do encounter.

Andreas Petzold, Romanesque Art is attractive, authoritative, readable. The emphasis here is on how the art worked within the society, so there are chapters on patronage, women, the Church, other cultures (Classical, Jewish, Islamic). Not much extended object-specific analysis, but an excellent primer on looking for the significance of works you do encounter.

George Zarnecki, Romanesque, has chapters on the different media: Architecture, Sculpture, Metalwork, Ivories, Stained Glass, Wall Painting, Book Illumination. The author takes us through the key features of each of these, and wears his enormous learning lightly. As with many older art books, this one challenges the reader by having illustrations on a different page from the text, so there is a good deal of flicking around which interrupts the reading. Well, we just have to get over it. The points Zarnecki makes in capsules about individual images (capital sculptures, for example) are outstanding.

Henri Focillon, The Art of the West 1: The Romanesque is a classic of art history. First published in 1938, it shows the author's appetite for dealing with whole cultures, whole centuries, looking for deep principles which help us to understand the individual object. Focillon writes wonderfully, in a style quite different to most approved art history. Of Romanesque imagery - bestiaries, strange distorted sculptures - he says: 'It seems, not the created world, but the dream of God on the eve of the Creation, a terrible first-draft of his plan'. Thoughts like that put a smile on your face and transform the act of seeing. Plenty to be learned here - as far as I can tell, it's not overly dated - and inspirational too.

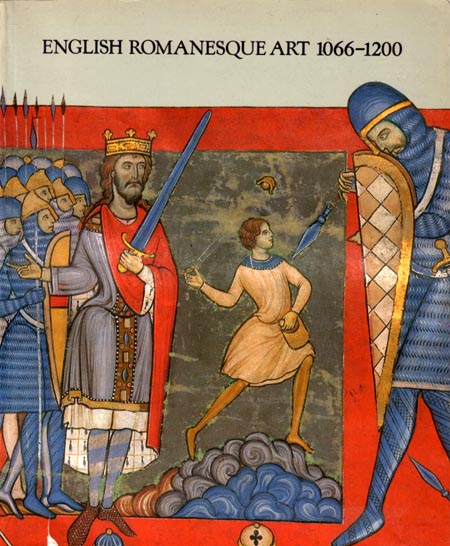

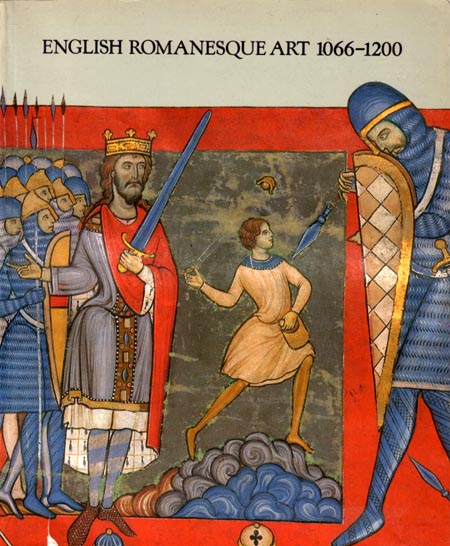

Zarnecki and other scholars produced English Romanesque Art 1066-1200, the catalogue which accompanied a major exhibition of Romanesque art from England, at the Hayward way back in 1984. All the arts are covered, and detailed descriptions of the exhibits make it a good source for getting to know particular works. Lots of information, perhaps best for occasional detailed reading.

Zarnecki and other scholars produced English Romanesque Art 1066-1200, the catalogue which accompanied a major exhibition of Romanesque art from England, at the Hayward way back in 1984. All the arts are covered, and detailed descriptions of the exhibits make it a good source for getting to know particular works. Lots of information, perhaps best for occasional detailed reading.

Anne Shaver-Crandell, Cambridge Introduction to Art: The Middle Ages is an excellent starting-point. Clear and helpful chapter on Romanesque.

Andreas Petzold, Romanesque Art is attractive, authoritative, readable. The emphasis here is on how the art worked within the society, so there are chapters on patronage, women, the Church, other cultures (Classical, Jewish, Islamic). Not much extended object-specific analysis, but an excellent primer on looking for the significance of works you do encounter.

Andreas Petzold, Romanesque Art is attractive, authoritative, readable. The emphasis here is on how the art worked within the society, so there are chapters on patronage, women, the Church, other cultures (Classical, Jewish, Islamic). Not much extended object-specific analysis, but an excellent primer on looking for the significance of works you do encounter.